- Home

- Patrice Chaplin

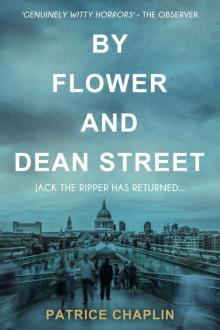

By Flower and Dean Street Page 6

By Flower and Dean Street Read online

Page 6

Overcome, she put the phone down. David ran up with his bottle, then stopped and stared at her, worried.

‘It’s all right. It’s all right,’ she murmured. Then she grabbed him and held him to her, tightly.

11

Feeling rather silly, Jane and Connie sat in the kitchen of a small untidy house in the suburbs, while a little homely woman bustled about making tea.

‘Is it a reading for both of you?’

‘No. Only my friend,’ said Jane. She dug Connie under the table and indicated her wedding-ring. Connie took it off.

‘Well, I charge 15 shillings a reading — or should I say 75 pence as it is in the new money? Is that all right? I’ve had to put my prices up a bit, I’m afraid.’

‘That’s all right,’ said Connie.

The woman beamed at her. ‘Well, we’ll get straight on, shall we? You don’t look too well,’ she said kindly. ‘But I won’t ask you any questions. Do you want your friend here, or would you prefer to be alone? She can sit in the living room. There’s a good fire.’

‘I’d rather she was here.’

The woman pulled up a chair and sat facing Connie, their knees almost touching, and instead of peering into the tea-leaves, as Connie had expected, she reached out, took Connie’s hands in hers and then gently let them go. Her eyes were shut, as she settled back in her chair.

She shivered. ‘Is it a cold day? I feel quite shivery suddenly. I expect you’ve come a long way.’

‘Quite a long way,’ Jane said brusquely.

‘How did you get my name, dear? I only ask because I don’t advertise, and I like to know how people come to me.’ She spoke normally, but her eyes were still shut.

‘From a girl who works with my friend — a teacher,’ said Connie softly.

Jane looked at Connie as though to say, ‘You’re giving yourself away.’

‘People come to me from all over. I don’t see many people any more as a rule, because I’m retired.’ Connie, prepared for another failure, relaxed back in her chair. Then the woman said, ‘But I thought I should see you. You probably wonder why I keep going on like this, but it’s as though I want to get away from that shivery feeling. I think that’s how you’ve been feeling lately. You keep doing things, going out, talking, you feel — oh, if I could only get back to the way it was before.’

‘Yes.’

The woman’s eyes were shut tight behind the thick pebble-glasses and she looked mottled, closed in like a tortoise.

‘Are you afraid of gas lamps, dear? I know it sounds a silly question, but that’s what I’m getting, so I have to ask you.’

‘No.’

‘Well, watch out for it, dear. I’m getting a lot of children here, oh, ever so many. Are they all yours? There’s nine. No. You’re too young. They don’t have such big families as they used to. That’s a funny thing to say, but I had to say it. Does it mean anything to you?’

‘No.’

‘There’s a gentleman here, older than you. A father perhaps. Are you married? I have to ask. Otherwise what I say next is going to sound rather rude.’

Ignoring Jane’s passionate signs she said, ‘Yes, I am married’, and she felt in her pocket for the ring.

‘Well, I don’t think I can really ask you anyway, because the question seems more for an older woman.’

‘Please ask me.’

‘Someone’s asking how many half-pennies you got from the last bloke. It’s funny, because half-pennies aren’t used any more. It’s funny as well because when I told you the price I said it in shillings, even though I’ve got so used to the new money I hardly ever make a mistake.’ She spoke quickly, as though embarrassed. ‘I feel you’re running, but whether it’s from someone or to them I can’t see. You’ve not been well lately. It’s not your body, more your — nerves. Have you been in hospital?’

Connie shook her head, forgetting completely the night she’d spent the month before.

‘Have you got a dog? Well, I can see someone offering you one. You’re not connected with the theatre, are you? I don’t mean as an actress, more in the wardrobe department.’

‘No.’

‘I see a lot of costumes. Old-fashioned dresses and shawls and boots and bonnets. Perhaps you’re going to get a job,’ she said brightly. ‘Do you wear gloves? No? I’ve got this older gentleman again. He’s, oh — I get a feeling of irritation. If he gets a bit short with you, you mustn’t mind. He’s worried, but he doesn’t know what to do. Is he a lot older than you?’

‘Thirteen years.’

‘Then he’s not this gentleman I’m getting now, because this one’s more your age. I see blackness all round this one. He comes out in the night. Does he work at night?’

‘Her husband often goes out at night,’ Jane cut in.

‘I get a feeling of dissatisfaction. Is that your husband?’

‘It might be.’

‘Terrible dissatisfaction. Frustration. I think it’s more this younger man. A job not finished. Does that mean anything to you?’

Connie shook her head.

‘He doesn’t wish you well, dear. I wish I could say he does.’

‘Who is he?’

‘He’s too vague for me to see him. He’s smart. Well turned out. He’s a long way off.’

‘Do I know him?’

‘You have known him. Just once.’

The kitchen was suddenly very depressing. The woman stopped talking. Even Jane was still.

Then the woman said, making an effort to be cheerful, ‘I get children going to school. I get only three. There should be four. One’s not well and stays at home.’

‘He’s too young to go to school.’

‘I think he should go to school. It would be better for him. Even a little nursery school.’

‘Why?’

The woman seemed to hesitate, then she looked directly at Connie. ‘When you’re not too well, dear, it upsets him. I want to sing a song. Oh, it’s ever such an old one.’ She looked at her lap. ‘It’s even before my time.

‘A smart and stylish girl you see,

Belle of good society;

Not too strict, but rather free

Yet as right as right can be.

Never forward, never bold

Not too hot and not too cold.

But the very thing I’m told

That in your arms you’ll like to hold.

Ta-ra-ra-Boom-de-ay.’

‘My voice isn’t very tuneful. You must excuse me. Does it mean anything to you?’

‘No.’

‘You haven’t said anything about her future,’ said Jane.

‘Well, I can only see a little way ahead with anyone.’ She looked at the window. ‘Anyway, it looks as though it’s brightened up a bit.’

*

They were both awake and staring into the dark.

‘Connie,’ he whispered.

‘Yes. I can’t sleep either.’

‘I think we should go away, right away this summer. What about Spain? I could take my holiday earlier.’

‘That would be lovely. But what about the summer-house for the back garden? You won’t have the money for both.’

‘I’ll do that next year. Have you taken the pills the quack gave you?’

‘Yes.’

‘I’m sure you haven’t. I wish you would. You’re still depressed. They’re supposed to be anti-depressants.’

‘I’d like David to go to nursery school.’

‘What?’

‘I think he’d enjoy it.’

‘Well — I — I’m not keen. No, Connie. We’ll have to think about that.’

They lay silent again. She felt she was almost asleep at last when he suddenly turned and got on top of her and started kissing her, passionately. She didn’t like it. The feeling got worse the more excited he got. She tried to sit up. She looked round her in the dark. She didn’t know quite where she was. The moment of alarm passed and she closed her eyes and relaxed. A different expression cam

e into her face — lewd, cunning — and she murmured something sexually provocative, something a prostitute might say, something she couldn’t have known. Daniel froze, then slapped her face hard.

Slowly he got off her and fumbled his way back to his place in the bed. They lay as before — separate, sleepless. Then she reached out and touched his hand and said, ‘I’m sorry. I don’t know what came over me. It felt different. I didn’t know where I was.’ She tried to laugh.

He didn’t respond. She lay still, tears streaming down her face.

12

Six weeks after Connie cut her armpit, she had to go back to the doctor for a second tetanus injection and what he called a check-up. Daniel had been phoning him non-stop. Jane came with her.

The waiting room — it was also his drawing room — was lived-in and pleasant, with enormous sagging brown chairs like old dogs humped in front of the fire. There were only tattered magazines on knitting and housecraft, so Jane opened the bookcase.

‘Do they go in for medical books! The Aberrations of — Can’t pronounce it. Ah! This looks interesting. Crime. My God! The pictures. Ugh! “Her head had been nearly severed from her body, the womb and two thirds of the — ” ’

‘Shut up!’

‘ “Had been pulled from her and left lying over her shoulder and — ” ’

‘Will you shut up, you bitch!’

Jane looked up. ‘Oh, I’m sorry. Christ! Is it upsetting you? I just thought —’

‘I’ve got to get some new shoes.’ Her voice was shrill. ‘I want some red ones with —’ Her foot tipped up. She stared at it.

Jane flopped on to a massive hairy chair, and its brown arms sank inwards and hugged her. She seemed quite unable not to read aloud. ‘Lobe of her right ear missing? What could he have wanted that for? No one knew who he was, you know.’

‘I don’t want to hear, goddamn you, Jane!’ Connie looked grey and drawn.

‘He used to creep up behind them — Good God! They mention Flower and Dean Street.’ Jane whipped over a page. ‘Help! He did two in one night. Elizabeth Stride. Throat cut. No mutilation. Possibly because he’d been interrupted by a hawker arriving with his horse and cart.’ She leapt up, leaving the chair lopsided. ‘Ah, here’s an interesting one.’

‘What does it say about that horse-and-cart one?’

‘This girl’s much more interesting. It took six hours in the mortuary to get her looking like a human —’

‘Go back to the other one!’ Connie’s voice, low and desperate, was hardly recognisable.

Jane, resentful at being dragged away from an attractive victim, took a long time finding the page. ‘Elizabeth Stride. Married in 1869 to a carpenter. Came from Sweden. In 1878, the pleasure steamer Princess Alice sank in the Thames and her husband and two of her nine children were drowned. She ended up in Flower and Dean Street, notorious for prostitutes, and was frequently arrested for being drunk. It doesn’t say much.’

Connie murmured, ‘Drowned ... drowned.’

‘Now with this other girl —’

‘Go back to Elizabeth Stride. What about her death?’

‘Just throat cut in Berners Street, 30th September, 1888. A hawker found her body at one a.m ... His horse shied with fright and probably disturbed the murderer who disappeared as if by some black magic before he could do anything worse. He had the desire, if that’s the right word, to remove bits of the body. A labourer said he saw her with a man shortly before she died and the man said, “You’d say anything but your prayers”. She was holding some grapes in her right hand and sweetmeats in the left.’

‘A dissatisfied gentleman,’ Connie said quietly.

‘Where are you going? Hey, Connie.’

Connie was on the pavement by the time Jane caught up with her. ‘What about your appointment? He needs, I mean wants, to see you. I’m sorry if I upset you. Heavens, you’re a dreadful colour.’ Connie seemed drained of blood — she could hardly walk. ‘You are upset. I wouldn’t have thought that would upset you.’

*

Connie insisted that Jane should go with her to Whitechapel; and Jane, although she said she thought it perverse, agreed. They took the 253 bus from Camden Town; it was a grey heavy afternoon and in that light Jane realised how Connie had changed. The laughter-lines at the corners of her eyes were wrinkles; her hair was lank; she no longer smelt of the summery perfume.

‘God, you’ve lost weight,’ said Jane.

Connie’s face was washed out, the beauty spot glaring. She’d tried to go back to the clairvoyant in the suburbs, but when the woman knew who it was she said she’d definitely retired, most definitely. Connie had asked quickly, ‘The man who didn’t wish me well. Does he want to kill me?’ And she had replied: ‘I didn’t get kill as much as steal.’

They trailed around the streets that had once been trailed around by the Ripper’s victims, and Jane, who was carrying her long bag full of racquets, asked, ‘Do you feel anything?’ Connie shook her head.

Jane stopped and took her arm. ‘You’ve got to admit it’s daft. We’ve done Flower and Dean Street twice, Berners Square three times.’ She started giggling. ‘I mean, if anyone knew what we’d been doing they’d lock us up.’

She laughed so much that Connie started too, and a man nearby stopped and stared at them.

‘Perhaps he’s the Ripper,’ said Jane, and they doubled up, helpless with laughter.

13

The summer seemed full of heavy grey afternoons. One Sunday towards the end of July, Mark, Daniel and Connie sat by a tennis court watching Jane play. The club tournament — today the women’s finals and Jane was winning. She was brown and lean, and she looked cooler than anyone around her, even the spectators. Connie watched Daniel watching her legs. It seemed to Connie that people had always noticed Jane’s flat chest — only noticed her flat chest — but now suddenly it was her thighs. Her thighs were riveting. She put a hand on his arm, but he took no notice and went on watching Jane.

After the match silver cups were distributed, and everyone drank lemonade and escaped from the exhausting heat outside into the stuffy cool of the clubhouse. Kids whizzed round the long tables piled with sandwiches and lurid cakes. Jane pushed up to Daniel, showed him her cup and waited foolishly for his approval. Mark elbowed his way through the crowds towards her, said Congratulations and was ignored. He attempted to kiss her, but someone got in the way.

‘It’s got to go back to have my name engraved on it. I got the doubles as well.’ She seemed weak with victory.

‘It’s a nice shape,’ said Daniel. ‘How does it feel to win?’

‘Terrific,’ and she hugged the cup.

As Connie was pouring lemonade for the children, she noticed Daniel in a corner, standing close to Jane, and it seemed to her that as they talked they were looking into each other’s eyes.

*

The next morning, early, Jane came swinging up the path. Connie, wearing a bikini, was tidying the kitchen, and when she saw her, she bent down fast and hoped to creep to the stairs without being seen. She did not want to talk to Jane. It was another grey thick day and she was deeply depressed.

Too late. Jane’s voice clattered into the kitchen. ‘What are you doing?’

‘Picking up something.’

‘Can you have the kid tonight?’

They stood silently looking at each other. Without her racquet Jane looked vaguely unsatisfactory.

‘Is Daniel in?’

Connie shook her head. Another silence.

‘I just wondered if he could sort out a point of law for me. It’s about HP,’ she said breathlessly. ‘I’m getting the washing-up machine on HP. It’s the only way to get it. Mark makes Scrooge look like the Gulbenkian Foundation.’ She started talking faster and louder. She hopped left-leg, right-leg, with an occasional yelp — she seemed much more her usual self.

‘I’m going to track down that magician.’

‘Oh no, Connie, don’t! Don’t be a fool. I mean, nothing’s happen

ed. I mean, the voices don’t warn you of anything. Mark says it’ll just wear off — vanish like poltergeists do. Anyway, I wouldn’t go near a magician. There’s a theory that the Ripper was a magician. He had to do five murders — the number 5 formed a pentagram — and then he’d be immune from discovery. He never was discovered ... Mark and I are going through a real wobbler. We fought all night. At least I did. He won’t. He locked himself in the kitchen. I’ve taken the key away. If he’s not careful I’ll take myself away. God, you’re lucky you’ve never had anything awful in your life.’

‘Will you help me find the magician?’

‘No. I’ve got too much on my mind. I’ve got my own problems. Concentrate on what you’ve got going for you. I think Mark and I are — finished. I’ve got that feeling.’

Connie stared out thoughtfully at the grey day.

*

Connie went back to the nightclub. A fire door was open and the beam of afternoon light showed up the whirling dust and made the red plush chairs and little pink table-lights tawdry. The owner, tired and irritable, stood smoking a cigar and watching a chorus girls’ audition. Connie, standing beside him, had finished her story and was waiting for a reply.

‘Danchenko? Danchenko? He’s not here.’

‘Do you know where I can find him?’

‘Why d’you want him? D’you want to book him?’ He turned and looked at her.

‘Yes. No.’

The man shrugged, and looked back at the girls. ‘He’s probably in New York.’

*

At the second theatrical agency a secretary said, ‘He’s not Hungarian. He comes from Tottenham. I can’t give you his address, but he’s appearing at the Spread Eagle in Barking.’

Seeing Connie’s reaction, she added, ‘It’s his slack season.’

*

That evening Connie got the children to bed early and made chilled cucumber soup, cheese soufflé and a crisp salad. She put on her yellow backless dress and her new platform shoes and served dinner in their rarely used dining room. The sideboard was full of flowers from the garden. There were long candles in elegant holders and iced white wine.

By Flower and Dean Street

By Flower and Dean Street